Thursday, March 04, 2010

Barnacle Dinner in the Galapagos

Working at an expansive range of underwater sites in the Galapagos, marine ecologist Jon Witman and his team found that at two sub-tidal depths, barnacle larvae had latched onto rock walls, despite the vertical currents. In fact, the stronger the vertical current, the more likely the barnacles would colonize a rocky surface.

The researchers also documented the presence of whelks and hogfish, which feast on barnacles. This predator-prey relationship shows that vertical upwelling zones are “much more dynamic ecosystems in terms of marine organisms than previously believed,” Witman said.

Scientists who study coastal marine communities had assumed that prey species such as barnacles and mussels would be largely absent in vertical upwelling areas, since the larvae, which float freely in the water as they seek a surface to attach to, would more likely be swept away in the coast-to-offshore currents. Studies of the near-surface layer of the water in rocky tidal zones confirmed that thinking. But the field work by Witman and his group, in deeper water than previous studies, told a different tale: Few barnacles were found on the plates in the weak upwelling zones, while plates at the strong upwelling sites were teeming with the crustaceans. Flourishing barnacle communities were found at both the 6-meter and 15-meter stations, the researchers reported.

The scientists think the free-floating larvae thrive in the vertical-current zones because they are constantly being bounced against the rocky walls and eventually find a tranquil spot in micro crevices in the rock to latch on to.

Further Reading

Coupling between subtidal prey and consumers along a mesoscale upwelling gradient in the Galápagos Islands. Jon D. Witman, Margarita Brandt, Franz Smith. Ecological Monographs 2010 80:1, 153-177

Brown University News, Barnacles Prefer Upwelling Currents, Enriching Food Chains in the Galapagos

Labels: Galapagos, marine biology, research, SCUBA News

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

Red Grouper create home for many animals

Researchers from Florida State University have found that Red Grouper (Epinephelus morio) dig out and maintain complex structures at the bottom of the sea. They remove sand, exposing hard rocks that are crucial to corals and sponges and the animals that rely on them. The work demonstrates that Red Groupers modify their environment, much as beavers do, creating habitat for many other animals including lobster and commercially important fish.

Researchers from Florida State University have found that Red Grouper (Epinephelus morio) dig out and maintain complex structures at the bottom of the sea. They remove sand, exposing hard rocks that are crucial to corals and sponges and the animals that rely on them. The work demonstrates that Red Groupers modify their environment, much as beavers do, creating habitat for many other animals including lobster and commercially important fish."Watching these fish dig holes was amazing enough,” says Felicia Coleman, lead researcher, “but then we realised that the sites served to attract mates, beneficial species such as cleaner shrimp that pick parasites and food scraps off the resident fish and a variety of prey species for the Red Grouper. So it's no surprise that the fish are remarkably sedentary. Why move if everything you need comes to you?”

“The research is incredibly valuable because it demonstrates how interconnected species are in the sea,” says Dr. Susan Williams, a professor at the University of California, Davis. “Red Groupers are the 'Frank Lloyd Wrights' of the sea floor because they are critical habitat architects. The species that associate with them include commercially valuable species- such as vermilion snapper, black grouper, and lobsters. If the groupers are overfished, the suite of species that depends on them is likely to suffer.”

Working along the West Florida Shelf, the authors observed the excavating behaviour of the Red Grouper during both their juvenile stage in inshore waters as their adult stage at depths of 100 m. The study serves to document this behaviour and its apparent impact on the biological diversity of the ocean. Their article on the study, “Benthic Habitat Modification through Excavation by Red Grouper, Epinephelus morio, in the Northeastern Gulf of Mexico,” is published in the most recent issue of the journal The Open Fish Science Journal.

Red Grouper (Epinephelus morio) is an economically important species in the reef fish community of the southeastern United States, and especially the Gulf of Mexico. It is relatively common in karst regions of the Gulf.

As juveniles, Red Grouper excavate the limestone bottom of Florida Bay and elsewhere, exposing “solution holes” formed thousands of years ago when sea level was lower, and freshwater dissolved holes in the rock surface. When sea level rose to its present state, these solution holes filled with sediment. By removing the sediment from these holes, Red Grouper restructure the flat bottom into a three dimensional matrix.

Spiny lobsters are among the many species that occupy these excavations, especially during the day when they need refuge from roving predators.

“What are the consequence of overfishing these habitat engineers?” asks co-author Koenig. “You can't remove an animal that can dig a hole five meters across and several meters deep to reveal the rocky substrate and expect there to be no effect on reef communities. The juveniles of a species closely associated with these pits, vermilion snapper, are extremely abundant around the offshore excavations. It is possible that the engineered habitat is significant as a nursery for this species, which other big fish rely on as food. One could anticipate a domino effect in lost diversity resulting from the loss of Red Grouper-engineered habitat.”

Red Grouper clearly remove sufficient sediment to transform an otherwise two-dimensional area into a three-dimensional structure below the seafloor, providing refuge for themselves and for other organisms. In the process, they expose hard substrate, thus creating settlement sites for corals, sponges, and anemones, allowing the creation of three-dimensional structure above the seafloor as well. Addition of these roles to their contribution as resident top predators suggests that they might have a disproportionately large per capita influence on the ecosystem within which they live.

Red Grouper have been harvested in the United States since the 1880s and are currently the most common grouper species landed in both commercial and recreational fisheries of the Gulf of Mexico.

Excessive fishery removals can and often do have cascading effects in marine communities that ultimately result in the loss of many species. This situation arises when the captured species has a disproportionately large influence on the system within which it lives. The Red Grouper has been shown to be one such species.

Further Reading:

Benthic Habitat Modification through Excavation by Red Grouper, Epinephelus morio, in the Northeastern Gulf of Mexico

pp.1-15 (15) Authors: Felicia C. Coleman, Christopher C. Koenig, Kathryn M. Scanlon, Scott Heppell, Selina Heppell, Margaret W. Miller

doi: 10.2174/1874401X01003010001

Florida State University

What do you think of this news item? Join a discussion.

Labels: America, coral, fish, marine biology, research, SCUBA News

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

Minke Whales Should Not be Culled

Antarctic minke whales are among the few species of baleen whales not decimated by commercial whaling during the 20th century, and some scientists have hypothesised that their large numbers are hampering the recovery of deleted species, such as blue, fin and humpback, which may compete for krill.

This “Krill Surplus Hypothesis” postulates that the killing of some two million whales in the Southern Ocean during the early- and mid-20th century resulted in an enormous surplus of krill, benefiting the remaining predators, including Antarctic minke whales.

But the new analysis, published this week in the journal Molecular Ecology, estimates that contemporary populations of minke whales are not “unusually abundant” in comparison with their historic numbers.

The Southern Ocean is one of the world’s largest and most productive ecosystems and in the 20th century went through what Scott Baker, a whale geneticist at Oregon State University, called “one of the most dramatic ‘experiments’ in ecosystem modification ever conducted.” The elimination of nearly all of the largest whales – such as the blue, fin and humpback – removed a huge portion of the biomass of predators in the ecosystem and changed the dynamics of predator-prey relationships.

Blue whales were reduced to about 1-2 percent of their previous numbers; fin whales to about 2-3 percent; and humpbacks to less than 5 percent. “The overall loss of large whales was staggering,” Baker said.

“It is possible that the removal of the larger whales would have meant more food for minkes,” Baker said, “but we don’t know much about the historic abundance of krill and whether the different whale species competed for it in the same places, or at the same time. It is possible that there might have been enough krill for all species prior to whaling.”

The scientists also say that current minke whale populations may be limited by other factors, including changes in sea ice cover.

“The bottom line is that the Krill Surplus Hypothesis does not appear to be valid in relation to minke whales and increasing hunting based solely on the assumption that minke whales are out-competing other large whale species would be a dubious strategy,” Baker said.

Further Reading: Oregon State University

What do you think of this news item? Join a discussion.

Labels: marine biology, research, SCUBA News, whale and dolphins

Monday, December 07, 2009

King Crab Family Grows

javascript:void(0)

The new species are Paralomis nivosa from the Philippines, P. makarovi from the Bering Sea, P. alcockiana from South Carolina, and Lithodes galapagensis from the Galapagos archipelago – the first and only king crab species yet recorded from the seas around the Galapagos Islands.

King crabs were first formally described in 1819. They include some of the largest crustaceans currently inhabiting the Earth. They are known from subtidal waters in cooler regions, but deep-sea species occur in most of the world’s oceans, typically living at depths between 500 and 1500 metres.

Many more species of King Crab remain to be discovered. “The oceans off eastern Africa, the Indian Ocean and the Southern Ocean are all particularly poorly sampled,” said Hall: “We need to know which king crab species live where before we can fully understand their ecology and evolutionary success.”

Further Reading

National Oceanography Centre, Southampton

What do you think of this news item? Join a discussion.

Labels: marine biology, research, SCUBA News

Thursday, November 05, 2009

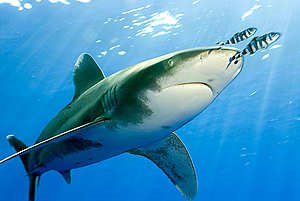

Tags reveal Great White Sharks' Beat

"White sharks are a large, highly mobile species," said researcher Salvador Jorgensen. "They can go just about anywhere they want in the ocean, so it's really surprising that their migratory behaviors lead to the formation of isolated populations."

Scientists with the Tagging of Pacific Predators (TOPP) program combined satellite tagging, passive acoustic monitoring and genetic tags to study great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) in the North Pacific. Details of their study are published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The fact that the northeastern Pacific white sharks undergo such a consistent, large-scale migration, and that they are all closely related and distinct from other known white shark populations, suggests that it is possible to conduct long-term population assessment and monitoring of these animals.

Barbara Block, professor of marine sciences at Stanford and a coauthor of the paper, said, "Catastrophic loss of large oceanic predators is occurring across many ecosystems. The white sharks' predictable movement patterns in the northeastern Pacific provide us with a super opportunity to establish the census numbers and monitor these unique populations. This can help us ensure their protection for future generations."

The researchers used a combination of satellite and acoustic tags to follow the migrations of 179 individual white sharks between 2000 and 2008. The tags reveal that the sharks spend the majority of their time in three areas of the Pacific: the North American shelf waters of California; the slope and offshore waters around Hawaii; and an area called the "White Shark Cafe," located in the open ocean approximately halfway between the Baja Peninsula and the Hawaiian Islands.

Genetics techniques were used to examine the relationships of the California sharks to all other white sharks examined globally. Studies of maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA sequences show that the populations are distinct, and suggest that the northeastern Pacific population may have been founded by a relatively small number of sharks in the late Pleistocene – within the last 200,000 years or so. The other populations of white sharks are concentrated near Australia and South Africa.

Depletion of top oceanic predators is a pressing global concern, particularly among sharks because they are slow reproducers. White sharks have been listed for international protection under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and the World Conservation Union (IUCN). Despite these precautionary listings, trade in white shark products, primarily fins, persists. Information on population and distribution of oceanic sharks is critical for implementing effective management efforts and the absence of such data impedes protection at all scales. Combining electronic tagging and genetic technologies can help protect sharks.

Further Reading:

Salvador J. Jorgensen, Carol A. Reeb, Taylor K. Chapple, Scot Anderson, Christopher Perle, Sean R. Van Sommeran, Callaghan Fritz-Cope, Adam C. Brown, A. Peter Klimley, and Barbara A. Block

Philopatry and migration of Pacific white sharks

Proc R Soc B 2009 : rspb.2009.1155v1-rspb20091155.

What do you think of this news item? Join a discussion.

Labels: marine biology, research, SCUBA News, sharks

Friday, October 09, 2009

Creature of the Month: Plumose Anemone

Plumose anemones (Metridium senile) occur in large numbers in good diving areas in temperate waters. They comprise a tall, smooth column topped with a crown of feathery tentacles. When they contact they look like swirly blobs, as can be seen in our photograph.

Plumose anemones (Metridium senile) occur in large numbers in good diving areas in temperate waters. They comprise a tall, smooth column topped with a crown of feathery tentacles. When they contact they look like swirly blobs, as can be seen in our photograph.Individuals may be white, orange, green or blue in colour. They grow up to 30 cm tall and 15 cm across at the base. They like areas with currents so tend to live on prominent pieces of wrecks or on rocky pinnacles.

With fine, delicate tentacles they are unsuited to capturing large animals like fish. Instead they specialise in smaller prey such as small planktonic crustaceans. The anemone's columnar body is narrower just below the tentacles. A current will bend the stalk at this point and expose the tentacles broadside to the flow in the best position for feeding on suspended matter.

With fine, delicate tentacles they are unsuited to capturing large animals like fish. Instead they specialise in smaller prey such as small planktonic crustaceans. The anemone's columnar body is narrower just below the tentacles. A current will bend the stalk at this point and expose the tentacles broadside to the flow in the best position for feeding on suspended matter. The Plumose anemone occurs from the Bay of Biscay (North of Spain) to Scandinavia in the northeast Atlantic, and on the west and east coasts of North America. It is unknown from the western basin of the Mediterranean but has been seen in the Adriatic, where it is believed to have been introduced. It has also been seen in Table Bay Harbour in South Africa where it was probably introduced from Europe.

The Plumose anemone occurs from the Bay of Biscay (North of Spain) to Scandinavia in the northeast Atlantic, and on the west and east coasts of North America. It is unknown from the western basin of the Mediterranean but has been seen in the Adriatic, where it is believed to have been introduced. It has also been seen in Table Bay Harbour in South Africa where it was probably introduced from Europe.

Further Reading:

Great British Marine Animals, by Paul Naylor

Ask Nature

What do you think of this news item? Join a discussion.

Labels: environment, Europe, marine biology, SCUBA diving, SCUBA News, SCUBA Travel, UK

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Killer Whales Die without Chinook Salmon

When you mention killer whales, the image of one ambushing a terrified seal often springs to mind. But there are populations of killer whales who live exclusively on fish. And not on just any fish: they are very specialised in which fish they will eat.

When you mention killer whales, the image of one ambushing a terrified seal often springs to mind. But there are populations of killer whales who live exclusively on fish. And not on just any fish: they are very specialised in which fish they will eat. According to research published in Biology Letters, two populations studied in the northeastern Pacific Ocean prefer to eat Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha). So much so that if the numbers of Chinook salmon drop this directly affects the numbers of killer whales. The whales seem unable to adopt a new food, become weak and have a higher mortality.

The authors conclude that other killer whale populations may be similarly constrained to one or two prey species, because the young whales will have learnt their fishing strategies from the rest of the group. They too will be limited in their ability to switch to new food if necessary.

Journal Reference:

John K. B. Ford, Graeme M. Ellis, Peter F. Olesiuk, and Kenneth C. Balcomb

Linking killer whale survival and prey abundance: food limitation in the oceans' apex predator?

Biol Lett 2009 : rsbl.2009.0468v1-rsbl20090468.

What do you think of this news item? Join a discussion.

Labels: fish, marine biology, SCUBA News, whale and dolphins

Friday, September 11, 2009

Rare Algae Saves Caribbean Coral

A rare opportunity has allowed a team of scientists to evaluate corals--and the essential, photosynthetic algae that live inside their cells--before, during, and after a period in 2005 when global warming caused sea-surface temperatures in the Caribbean to rise.

A rare opportunity has allowed a team of scientists to evaluate corals--and the essential, photosynthetic algae that live inside their cells--before, during, and after a period in 2005 when global warming caused sea-surface temperatures in the Caribbean to rise.The team, led by Penn State biologist Todd LaJeunesse, found that a rare species of algae that is tolerant of stressful environmental conditions proliferated in corals at a time when more sensitive algae that usually dwell within the corals were being expelled.

Certain species of algae have evolved over millions of years to live in symbiotic relationships with species of corals. These photosynthetic algae provide the corals with nutrients and energy, while the corals provide the algae with a place to live.

"There is a fine balance between giving and taking in these symbiotic relationships," said LaJeunesse.

Symbiodinium trenchi is normally a rare species of algae in the Caribbean, according to LaJeunesse. "Because the species is apparently tolerant of high or fluctuating temperatures, it was able to take advantage of a 2005 warming event and become more prolific."

Symbiodinium trenchi appears to have saved certain colonies of coral from the damaging effects of unusually warm water.

"As ocean temperatures rise as a result of global warming, we can expect this species to become more common and persistent," said LaJeunesse. "However, since it is not normally associated with corals in the Caribbean, we don't know if its increased presence will benefit or harm corals in the long term."

If Symbiodinium trenchi takes from the corals more than it gives back, over time the corals' health will decline.

In 2005, sea surface temperatures in the Caribbean rose by up to two degrees Celsius above normal for a period of three to four months, high enough and long enough to severely stress corals.

The process of damaged or dying algae being expelled from the cells of corals is known as bleaching because it leaves behind bone-white coral skeletons that soon will die without their symbiotic partners.

Although Symbiodinium trenchi saved some corals from dying in 2005, LaJeunesse is concerned that the species might not be good for the corals if warming trends continue and Symbiodinium trenchi becomes more common.

"Because Symbiodinium trenchi does not appear to have successfully co-evolved with Caribbean coral species, it may not provide the corals with adequate nutrition," he said.

The research was published in the online version of the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B on September 9, 2009.

What do you think of this news item? Join a discussion.

Labels: Caribbean, coral, environment, marine biology, research, SCUBA News

Wednesday, July 15, 2009

Creature of the Month: Dragonet, Callionymus lyra

One hundred and eighty-six species of the "Little Dragon" fish live from Iceland in the North to the Indo-Pacific oceans in the South. You will find the species we are concentrating on today, Callionymus lyra, from Norway to Senegal: in the Eastern Atlantic and the North, Irish, Mediterranean, Black, Baltic, Aegean and other Seas.

The adult male C. lyra is colourfully patterned in orange and blue. The females are smaller and a mottled brown. They have an interesting courtship ritual. The male performs an elaborate display, darting around the female, spreading his brightly coloured fins and pulling faces! If the female is impressed the pair then swim side-by-side, almost vertically up to the surface. There they release the eggs and sperm into the water, spawning at dusk. Dragonet males are thought to mate only once in a lifetime.

Dragonets spend most of their lives on sandy or rocky bottoms. They live from the shallows down to 100 m. They are sometimes confused with gobies but have a much broader triangular, head and a long dorsal ray on their backs. If you see slender fish meeting this description darting away from you on the bottom it is probably a dragonet.

Further Reading:

Great British Marine Animals, by Paul Naylor

Labels: fish, marine biology, SCUBA diving, SCUBA News, SCUBA Travel, UK

Thursday, June 25, 2009

Third of Pelagic Sharks Threatened with Extinction

The first study to determine the global conservation status of 64 species of open ocean (pelagic) sharks and rays reveals that 32 percent are threatened with extinction, primarily due to overfishing, according to the IUCN Shark Specialist Group.

The first study to determine the global conservation status of 64 species of open ocean (pelagic) sharks and rays reveals that 32 percent are threatened with extinction, primarily due to overfishing, according to the IUCN Shark Specialist Group.“Despite mounting threats, sharks remain virtually unprotected on the high seas,” says Sonja Fordham, Deputy Chair of the IUCN Shark Specialist Group and Policy Director for the Shark Alliance. “The vulnerability and lengthy migrations of most open ocean sharks mean they need coordinated, international conservation plans. Our report documents serious overfishing of these species, in national and international waters, and demonstrates a clear need for immediate action on a global scale.”The report comes days before Spain hosts an international summit of fishery managers responsible for high seas tuna fisheries in which sharks are taken without limit. It also coincides with an international group of scientists meeting in Denmark to formulate management advice for Atlantic porbeagle sharks.

The study reports the Great Hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran) and Scalloped Hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini) sharks, as well as Giant Devil Rays (Mobula mobular), as globally Endangered and facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild. Smooth Hammerheads (Sphyrna zygaena), Great White (Carcharodon carcharias), Basking (Cetorhinus maximus), Oceanic Whitetip (Carcharhinus longimanus), two species of Mako (Isurus spp.) and three species of Thresher (Alopias spp.) sharks are classed as globally Vulnerable to extinction ( facing a high risk of extinction in the wild).

Scalloped hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini)

(Image: Simon Rogerson)

Many open ocean sharks are taken mainly in high seas tuna and swordfish fisheries. Once considered only incidental “bycatch”, these species are increasingly targeted due to new markets for shark meat and high demand for their valuable fins, used in the Asian delicacy shark fin soup. To source this demand, the fins are often cut off sharks and the rest of the body is thrown back in the water, a process known as “finning”. Finning bans have been adopted for most international waters, but lenient enforcement standards hamper their effectiveness.

Oceanic Whitetip (Carcharhinus longimanus)

(Image: Simon Rogerson)

Sharks are particularly sensitive to overfishing due to their tendency to take many years to mature and have relatively few young. In most cases, pelagic shark catches are unregulated or unsustainable.

The IUCN Shark Specialist Group is calling on governments to set catch limits for sharks and rays based on scientific advice and the precautionary approach. It further urges governments to fully protect Critically Endangered and Endangered species of sharks and rays, ensure an end to shark finning and improve the monitoring of fisheries taking sharks and rays.

Silky (Carcharhinus falciformis)

(Image: Jeremy Stafford-Deitsch)

The IUCN uses a series of categories to classify species

| EXTINCT | The last individual has died |

| EXTINCT IN THE WILD | Only survives in captivity or cultivation |

| CRITICALLY ENDANGERED | Facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild |

| ENDANGERED | Facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild |

| VULNERABLE | Facing a high risk of extinction in the wild |

| NEAR THREATENED | Likely to qualify for, a threatened category in the near future |

| LEAST CONCERN | Does not qualify for any of the above |

is the world’s largest global environmental network. It is a

membership union with more than 1,000 government and

non-governmental member organisations and almost 11,000

volunteer scientists in more than 160 countries.

Further Reading:

The Conservation Status of Pelagic Sharks and Rays: Report of the IUCN Shark Specialist Group Pelagic Shark Red List Workshop

IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria booklet

Related Stories:

EU launches shark protection plan

Caribbean Big Fish Disappearing

Mediterranean Sharks Declining Fast

Mexico Passes Shark Finning Ban

Four Times more Sharks caught than Officially Reported

What do you think of this news item? Join a discussion.

Labels: fish, marine biology, research, SCUBA News, sealife, sharks

Wednesday, April 01, 2009

Antarctic marine biodiversity data now online

New web portal provides free and open access to information on antarctic marine species. The SCAR-MarBIN portal lets users browse, see and search different types of data, including over 2000 photos and videos. Entries are geo-referenced so users can discover what is found where.

New web portal provides free and open access to information on antarctic marine species. The SCAR-MarBIN portal lets users browse, see and search different types of data, including over 2000 photos and videos. Entries are geo-referenced so users can discover what is found where. The database now offers access to over one million records from 120 datasets. This was one of the ambitious objectives for the end of the International Polar Year (IPY). The data is updated by more than 70 experts worldwide. SCAR-MarBIN makes it possible to instantly download data and map the occurrence and abundance of polar marine organisms.

Antarctic marine ecosystems are particularly challenged by Global changes. More and more, the Southern Ocean is considered as a hotbed of marine speciation, having a considerable influence on Marine ecosystems worldwide.

SCAR-MarBIN is the information partner of the Census of Antarctic Marine Life (CAML), one of 17 projects of the Census of Marine Life.

What do you think of this news item? Join a discussion.

Labels: marine biology, SCUBA News, sealife

Friday, March 27, 2009

Crabs feel and remember pain

New research published by a Queen's University academic has shown that crabs not only suffer pain but that they retain a memory of it.

New research published by a Queen's University academic has shown that crabs not only suffer pain but that they retain a memory of it.The study, published in the journal Animal Behaviour, looked at the reactions of hermit crabs to small electric shocks. It was was carried out by Professor Bob Elwood and Mirjam Appel from the School of Biological Sciences at Queen's University Belfast.

Professor Elwood, who previously carried out a study showing that prawns endure pain, said his research highlights the need to investigate how crustaceans used in food industries are treated.

Hermit crabs have no shell of their own so inhabit other structures, usually empty mollusc shells. When the crab becomes to large for its current shell, it looks for another. When it finds a likely looking one, it will try it on. If the shell doesn't fit, or is too heavy, the crab returns to its old shell and continues it search. Where there is a large population of hermit crabs and a shortage of shells, the crab will accept a sub-standard home: maybe a cracked or uncomfortable shell. But in good conditions it will be very particular about the new shell it chooses.

During the research wires were attached to shells to deliver the small shocks to the abdomen of the some of the crabs within the shells.

The only crabs to get out of their shells were those which had received shocks, indicating that the experience is unpleasant for them.

Hermit crabs are known to prefer some species of shells to others and it was found that that they were more likely to come out of the shells they least preferred. This shows that central neuronal processing occurs rather than the response merely being a reflex. They traded-off between keeping a good shell and acceptance of the shock.

Crabs that had been shocked but had remained in their shell appeared to remember the experience of the shock because they quickly moved towards the new shell, investigated it briefly and were more likely to change to the new shell compared to those that had not been shocked.

Professor Elwood said: “There has been a long debate about whether crustaceans including crabs, prawns and lobsters feel pain. “We know from previous research that they can detect harmful stimuli and withdraw from the source of the stimuli but that could be a simple reflex without the inner ‘feeling’ of unpleasantness that we associate with pain.

“This research demonstrates that it is not a simple reflex but that crabs trade-off their need for a quality shell with the need to avoid the harmful stimulus.

“Such trade-offs are seen in vertebrates in which the response to pain is controlled with respect to other requirements.

“Humans, for example, may hold on a hot plate that contains food whereas they may drop an empty plate, showing that we take into account differing motivational requirements when responding to pain.

“Trade-offs of this type have not been previously demonstrated in crustaceans. The results are consistent with the idea of pain being experienced by these animals.”

Professor Elwood says that in contrast to mammals, little protection is given to the millions of crustaceans that are used in the fishing and food industries each day. He added "Millions of crustacean are caught or reared in aquaculture for the food industry. There is no protection for these animals (with the possible exception of certain states in Australia) as the presumption is that they cannot experience pain.

Journal Reference:

Robert W. Elwood and Mirjam Appel, Pain experience in hermit crabs?, Animal Behaviour (2009), doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.01.028.

-

What do you think of this news item? Join a discussion.

Labels: marine biology, research, SCUBA News

Thursday, January 08, 2009

CO2 emissions harm jumbo squid

The researchers subjected the squids (Dosidicus gigas) to elevated concentrations of CO2 equivalent to those likely to be found in the oceans in 100 years due to anthropogenic emissions. They found that the squid’s routine oxygen consumption rate was reduced under these conditions, and their activity levels declined, presumably enough to have an effect on their feeding behavior.

Jumbo squid are an important predator in the eastern Pacific Ocean, and they are a large component of the diet of marine mammals, seabirds and fish.

According to Seibel, jumbo squid migrate between warm surface waters at night where CO2 levels are increasing and deeper waters during the daytime where oxygen levels are extremely low.

“Squids suppress their metabolism during their daytime foray into hypoxia, but they recover in well-oxygenated surface waters at night,” he said. “If this low oxygen layer expands into shallower waters, the squids will be forced to retreat to even shallower depths to recover. However, warming temperatures and increasing CO2 levels may prevent this. The band of habitable depths during the night may become too narrow.”

Carbon dioxide enters the ocean via passive diffusion from the atmosphere in a process called ocean acidification. This phenomenon has received considerable attention in recent years for its effects on calcifying organisms, such as corals and shelled mollusks, but the study by Seibel and Rosa is one of the first to show a direct physiological effect in a non-calcifying species.

The scientists speculate that the squids may eventually migrate to more northern climes where lower temperatures would reduce oxygen demand and relieve them from CO2 and oxygen stress. While it is possible, they say, that the squids could adjust their physiology over time to accommodate the changing environment, jumbo squids have among the highest oxygen demands of any animal on the planet and are thus fairly constrained in how they can respond.

“We believe it is the blood that is sensitive to high CO2 and low pH,” Seibel said. “This sensitivity allows the squids to off-load oxygen more effectively to muscle tissues, but would prevent the squid from acquiring oxygen across the gills from seawater that is high in CO2.”

While many other squid and octopus species have oxygen transport systems that are equally sensitive to pH, few have such high oxygen demand coupled with large body size and low environmental oxygen. Therefore the scientists believe that their study results should not be extrapolated to other marine animals.

Further reading: University of Rhode Island

What do you think of this news item? Start a discussion.

Labels: environment, marine biology, research

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

Sea snakes drink only freshwater

Sea snakes may slither in saltwater, but they sip the sweet stuff.

So concludes a University of Florida zoologist in a paper appearing this month in the online edition of the November/December issue of the journal Physiological and Biochemical Zoology.

Harvey Lillywhite says it has been the “long-standing dogma” that the roughly 60 species of venomous sea snakes worldwide satisfy their drinking needs by drinking seawater, with internal salt glands filtering and excreting the salt. Experiments with three species of captive sea kraits captured near Taiwan, however, found that the snakes refused to drink saltwater even if thirsty — and then would drink only freshwater or heavily diluted saltwater.

“Our experiments demonstrate they actually dehydrate in sea water, and they’ll only drink freshwater, or highly diluted brackish water with small concentrations of saltwater — 10 to 20 percent,” Lilywhite said.

Harold Heatwole, a professor of zoology at North Carolina State University and expert on sea snakes, termed Lillywhite’s conclusion “a very significant finding.”

“This result probably holds the key to understanding the geographic distribution of sea snakes,” Heatwole said.

The research may help explain why sea snakes tend to have patchy distributions and are most common in regions with abundant rainfall, Lillywhite said. Because global climate change tends to accentuate droughts in tropical regions, the findings also suggest that at least some species of sea snakes could be threatened now or in the future, he added.

“There may be places where sea snakes are barely getting enough water now,” he said. “If the rainfall is reduced just a bit, they’ll either die out or have to move.”

Sea snakes are members of the elapid family of snakes that also includes cobras, mambas and coral snakes. They are thought to have originated as land-dwelling snakes that later evolved to live in oceans. Most spend all, or nearly all, of their lives in seawater, including giving birth to live young while swimming. A minority, including the kraits that Lillywhite studied, lay eggs and spend at least a small part of their lives on land.

Lillywhite believes the sea snakes that spend their lives in the open ocean drink water from the “lens” of freshwater that sits atop saltwater during and after rainfall, before the two have had a chance to mix. That would explain why some seawater lagoons, where the waters are calmer due to protection from reefs, are home to dense populations of sea snakes — the freshwater lens persists for longer periods before mixing into saltwater.

Rather than helping sea snakes gain water, the snakes’ salt gland may help the snakes with ion balance — moving excess salts from the bloodstream, Lillywhite said.

Some sea snake species living in dry regions may already be suffering as a result of climate change. Lillywhite said a colleague in Australia, which is in the midst of a historic drought, has observed declines and possible extinctions in some species at Ashmore Reef, home to the most diverse and abundant population of sea snakes in the world.

“We are trying to look at rainfall in that region and see if there is a correlation,” Lillywhite said.

He added that his findings also raise questions about the accepted wisdom that other marine reptiles, including sea turtles, satisfy their freshwater needs by drinking saltwater.

Labels: environment, marine biology, research

Friday, July 11, 2008

One Third of Reef-Building Corals Face Extinction

One third of reef-building corals around the world are threatened with extinction, according to the first-ever comprehensive global assessment to determine their conservation status. The study findings were published yesterday by Science Express.

One third of reef-building corals around the world are threatened with extinction, according to the first-ever comprehensive global assessment to determine their conservation status. The study findings were published yesterday by Science Express.Leading coral experts joined forces with the Global Marine Species Assessment (GMSA) – a joint initiative of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and Conservation International (CI) – to apply the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria to this important group of marine species.

“The results of this study are very disconcerting,” stated Kent Carpenter, lead author of the Science article, GMSA Director, IUCN Species Programme. “When corals die off, so do the other plants and animals that depend on coral reefs for food and shelter, and this can lead to the collapse of entire ecosystems.”

Built over millions of years, coral reefs are home to more than 25 percent of marine species, making them the most biologically diverse of marine ecosystems. Corals produce reefs in shallow tropical and sub-tropical seas and have been shown to be highly sensitive to changes in their environment.

Researchers identified the main threats to corals as climate change and localized stresses resulting from destructive fishing, declining water quality from pollution, and the degradation of coastal habitats. Climate change causes rising water temperatures and more intense solar radiation, which lead to coral bleaching and disease often resulting in mass coral mortality.

Shallow water corals have a symbiotic relationship with algae called zooxanthellae, which live in their soft tissues and provide the coral with essential nutrients and energy from photosynthesis and are the reason why corals have such beautiful colors. Coral bleaching is the result of a stress response, such as increased water temperatures, whereby the algae are expelled from the tissues, hence the term “bleaching.” Corals that have been bleached are weaker and more prone to attack from disease. Scientists believe that increased coral disease also is linked to higher sea temperatures and an increase in run-off pollution and sediments from the land.

Researchers predict that ocean acidification will be another serious threat facing coral reefs. As oceans absorb increasing amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, water acidity increases and pH decreases, severely impacting corals’ ability to build their skeletons that form the foundation of reefs.

The 39 scientists who co-authored this study agree that if rising sea surface temperatures continue to cause increased frequency of bleaching and disease events, many corals may not have enough time to replenish themselves and this could lead to extinctions.

“These results show that as a group, reef-building corals are more at risk of extinction than all terrestrial groups, apart from amphibians, and are the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change,” said Roger McManus, CI’s vice president for marine programs. “The loss of the corals will have profound implications for millions of people who depend on coral reefs for their livelihoods.”

Coral reefs harbor fish and other marine resources important for coastal communities. They also help protect coastal towns and other near-shore habitats from severe erosion and flooding caused by tropical storms.

Staghorn (Acroporid) corals face the highest risk of extinction, with 52 percent of species listed in a threatened category. The Caribbean region has the highest number of highly threatened corals (Endangered and Critically Endangered), including the iconic elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) which is listed as Critically Endangered. The high biodiversity “Coral Triangle” in the western Pacific’s Indo-Malay-Philippine Archipelago has the highest proportions of Vulnerable and Near-Threatened species in the Indo-Pacific, largely resulting from the high concentration of people living in many parts of the region.

Corals from the genera Favia and Porites were found to be the least threatened due to their relatively higher resistance to bleaching and disease. In addition, 141 species lacked sufficient information to be fully assessed and were therefore listed as Data Deficient. However, researchers believe that many of these species would have been listed as threatened if more information were available.

The results emphasize the widespread plight of coral reefs and the urgent need to enact conservation measures. “We either reduce our CO2 emission now or many corals will be lost forever,” says Julia Marton-Lefèvre, IUCN Director General. “Improving water quality, global education and the adequate funding of local conservation practices also are essential to protect the foundation of beautiful and valuable coral reef ecosystems.”

Coral experts participated in three workshops to analyze data on 845 reef-building coral species, including population range and size, life history traits, susceptibility to threats, and estimates of regional coral cover loss.

The reef-building corals assessment is one group of a number of strategic global assessments of marine species the GMSA has been conducting since 2006 at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia. Other assessments are being conducted on seagrasses and mangroves that are also important habitat-forming species, all marine fishes, and other important keystone invertebrates. By 2012, the GMSA plans to complete its comprehensive first stage assessment of the threat of extinction for over 20,000 marine plants and animals, providing an essential baseline for conservation plans around the world, and tracking the extinction risk of marine species.

The results of the coral species assessment will be placed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in October 2008. Currently, the assessments can be found at

http://www.sci.odu.edu/gmsa/about/corals.shtml

What do you think of this news item? Start a discussion.

Bookmark with: del.icio.us | Digg | Newsvine | NowPublic | Reddit

|

--

Subscribe to SCUBA News (ISSN 1476-8011) for more free news, articles, diving reports and marine life descriptions - http://www.scubatravel.co.uk/news.html

Labels: coral, coral reef, environment, marine biology, research

Monday, July 07, 2008

Cleaner fish create safe havens

Both cleaner and cleaned fish benefit from this behaviour. Cleaner fish are also thought to benefit from immunity to predation. They stroke their "clients'" with their fins to help persuade the predators not to eat them. Researchers in Australia have found that the more stroking the calmer the predator. And it wasn't just the cleaner fish who benefited. Other fish nearby the cleaner station experienced less aggressive behaviour from the predators. The suggests that cleaner stations act as safe havens from predator aggression.

Further Reading: Behavioral Ecology, doi:10.1093/beheco/arn067

Cleaner fish do clean!

--

What do you think of this news item? Start a discussion.

Bookmark with: del.icio.us | Digg | Newsvine | NowPublic | Reddit

|

--

Subscribe to SCUBA News (ISSN 1476-8011) for more free news, articles, diving reports and marine life descriptions - http://www.scubatravel.co.uk/news.html

Labels: fish, marine biology, research, sealife

Wednesday, March 12, 2008

Global warming turns fish deaf

Is it important that global warming turns fish deaf? Yes. For coral reef fish, sound is vital for them to judge where to settle down and live.

Is it important that global warming turns fish deaf? Yes. For coral reef fish, sound is vital for them to judge where to settle down and live.After hatching, reef fish larvae are dispersed by ocean currents for a few weeks. The larval fish must then find their way back to a suitable reef to make their home.

It's thought that the young fish home in on high-frequency noises. Coral reefs are extremely noisy environments, with the crackle of snapping shrimps and the chatter of fish set against a backdrop of wind, rain and surf. Sound carries well underwater, and most fish have great hearing.

Global warming and more acidic oceans, though, can cause fish to be born with deformed earbones. Reasearchers at the Australian Institute of Marine Science in Townsville and the University of Edinburgh, suspected that it might be harder for these fish to pinpoint the origin of a sound, increasing the chance they would get lost in the ocean. And, indeed, their results show that this is so.

Journal References and Further Reading:

Proceedings of the Royal Society, Volume 275, Number 1634 / March 07, 2008

Animal Behaviour, doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.11.004

SOUND: The essential navigation cue for young reef fishes to find their way home

--

What do you think of this news item? Start a discussion.

Bookmark with: del.icio.us | Digg | Newsvine | NowPublic | Reddit

|

--

Subscribe to SCUBA News (ISSN 1476-8011) for more free news, articles, diving reports and marine life descriptions - http://www.scubatravel.co.uk/news.html

Labels: coral reef, environment, fish, marine biology, research, sealife

Wednesday, March 05, 2008

Scientists Reveal First-Ever Global Map of Total Human Effect on Oceans

More than 40 percent of the world's oceans are heavily affected by human activities, and few if any areas remain untouched, according to the first global-scale study of human influence on marine ecosystems.

More than 40 percent of the world's oceans are heavily affected by human activities, and few if any areas remain untouched, according to the first global-scale study of human influence on marine ecosystems.By overlaying maps of 17 different activities such as fishing, climate change and pollution, the researchers have produced a composite map of the toll that humans have exacted on the seas.

The work, published in Science, was conducted at the National Science Foundation (NSF)'s National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS) at the University of California at Santa Barbara, and involved 19 scientists from a range of universities, NGOs, and government agencies.

The study synthesized global data on human impacts to marine ecosystems such as coral reefs, seagrass beds, continental shelves and the deep ocean.

"This research is a critically needed synthesis of the impact of human activity on ocean ecosystems," said David Garrison, biological oceanography program director at NSF. "The effort is likely to be a model for assessing these effects at local and regional scales."

Past studies have focused largely on single activities or single ecosystems in isolation, and rarely at the global scale. In this study the scientists were able to look at the summed influence of human activities across the entire ocean.

"This project allows us to finally start to see the big picture of how humans are affecting the oceans." said lead scientist Ben Halpern of NCEAS. "Our results show that when these and other individual impacts are summed up, the big picture looks much worse than I imagine most people expected. It was certainly a surprise to me."

The study reports that the most heavily affected waters in the world include large areas of the North Sea, the South and East China Seas, the Caribbean Sea, the east coast of North America, the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Bering Sea and several regions in the western Pacific. The least affected areas are largely near the poles.

Human influence on the ocean varies dramatically across various ecosystems. The most heavily affected areas include coral reefs, rocky reefs and seamounts. The least impacted ecosystems are soft-bottom areas and open-ocean surface waters.

"My hope is that these results serve as a wake-up call to better manage and protect our oceans, rather than a reason to give up," added Halpern.

-

What do you think of this news item? Start a discussion.

Bookmark with: del.icio.us | Digg | Newsvine | NowPublic | Reddit

|

--

Subscribe to SCUBA News (ISSN 1476-8011) for more free news, articles, diving reports and marine life descriptions - http://www.scubatravel.co.uk/news.html

Labels: environment, marine biology, research

Tuesday, March 04, 2008

Turtles at risk from non-stick pans

The same chemicals that keep food from sticking to our frying pans and stains from setting in our carpets are damaging the livers and impairing the immune systems of loggerhead turtles - an environmental health impact that also may signal a danger for humans.

The same chemicals that keep food from sticking to our frying pans and stains from setting in our carpets are damaging the livers and impairing the immune systems of loggerhead turtles - an environmental health impact that also may signal a danger for humans.A scientific team monitoring the blood plasma of loggerhead turtles along the U.S. East Coast consistently found significant levels of perfluorinated compounds (PFCs). PFCs are used as nonstick coatings and additives in a wide variety of goods including cookware, furniture fabrics, carpets, food packaging, fire-fighting foams and cosmetics. They are very stable, persist for a long time in the environment and are known to be toxic to the liver, reproductive organs and immune systems of laboratory mammals.

PFC concentrations measured in the plasma of turtles found along the coast from Florida to North Carolina indicated that PFCs have become a major contaminant for the species. The levels of the most common PFC, perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), were higher in turtles captured in the north than in the south. Data recently evaluated by NIST and College of Charleston graduate student Steven O’Connell shows that this northern trend of higher PFOS concentrations continues up into the Chesapeake Bay.

Blood chemistry analyses of PFC-contaminated loggerheads suggested damage to liver cells and the suppression of at least one immune function which could lead to a higher risk of disease. To support the “cause-effect relationship” between PFCs and illness, the researchers exposed Western fence lizards to the same PFOS levels found in loggerheads in the wild. The lizards showed significant increases in an enzyme that indicates liver toxicity. They also had signs of suppressed immune function.

These findings, Keller said, indicate that current environmental PFC exposures—at concentrations comparable to those seen in human blood samples—are putting marine species at enhanced risk of health problems from reduced immunity and may suggest a similar threat to us.

Keller reported that a recently completed study led by colleague Margie Peden-Adams of the Medical University of South Carolina that showed PFOS is toxic to the immune systems of mice at concentrations found both in loggerhead sea turtles and humans. The ability of the mouse immune system to respond to a challenge was reduced in half by PFOS—and this occurred at the lowest level of the compound ever reported for a toxic effect.

Further Reading: NIST Tech Beat

-

What do you think of this news item? Start a discussion.

Bookmark with: del.icio.us | Digg | Newsvine | NowPublic | Reddit

|

--

Subscribe to SCUBA News (ISSN 1476-8011) for more free news, articles, diving reports and marine life descriptions - http://www.scubatravel.co.uk/news.html

Labels: marine biology, research, turtles

Monday, September 24, 2007

Blue Tang is Creature of the Month

Blue Tangs are often found roaming the reef, in search of their favourite food - algae. They are surgeonfish which may appear either singly or in large schools, which can contain hundreds of individuals.

The name surgeonfish comes from the defensive spines located on the caudal peduncle (the part of the fish between the tail and the rest of the body) which are as sharp as a surgeon's scalpel. They are herbivorous, eating plants and algae, so their spines are used only for defense.

Blue Tangs are sometimes found schooling with other members of the surgeonfish family. These schools form around dusk when nocturnal predators, such as moray eels, begin to hunt. These schools provoke an aggressive reaction from the smaller damselfishes defending patches of algae.

The true Blue Tang is Acanthurus coeruleus, which found in the Caribbean Sea. Other fish are also sometimes referred to as Blue Tang. In the Red Sea, for example, there is Zebrasoma xanthurum, more properly known as Yellowtail Tang. Also in the Indo-Pacific masquerading as Blue Tang is the Palette Surgeon, Paracanthurus hepatus; familiar if you've watched the "Finding Nemo" film.

As you might expect, blue tangs are largely blue. The Caribbean Blue Tang, Acanthurus coeruleus, has a bright yellow or white spine. It lives between 3 and 28 m on rocky or coral reefs. As it is unafraid of divers you can usually get quite close to it.

The Blue Tang, and other surgeonfish, are important on a shallow coral reef because they help keep the algae in check. Without them the algae would grow so fast that coral larvae settling and trying to make a start on the reef would soon be overgrown.

Further reading:

Beautiful Oceans Coral Reef Architecture & Organisms,

The Blue Planet

What do you think of this news item? Start a discussion.

Bookmark with: del.icio.us | Digg | Newsvine | NowPublic | Reddit

|

--

Subscribe to SCUBA News (ISSN 1476-8011) for more free news, articles, diving reports and marine life descriptions - http://www.scubatravel.co.uk/news.html

Labels: fish, marine biology, sealife